You don't have to understand poetry in order to enjoy it. But today, the skill of reading poetry is getting lost. Speed-reading, AI summaries and bullet-point lists have destroyed our ability to read in silent images, to enjoy the feeling of words, to not always search for their meaning. I am Andy, philosophy lecturer, and I have been reading and loving poetry for almost fifty years. And in this episode, I will show you how you can also open up a whole new world of poems for yourself, to read and enjoy and get happiness and meaning from, in your everyday life.

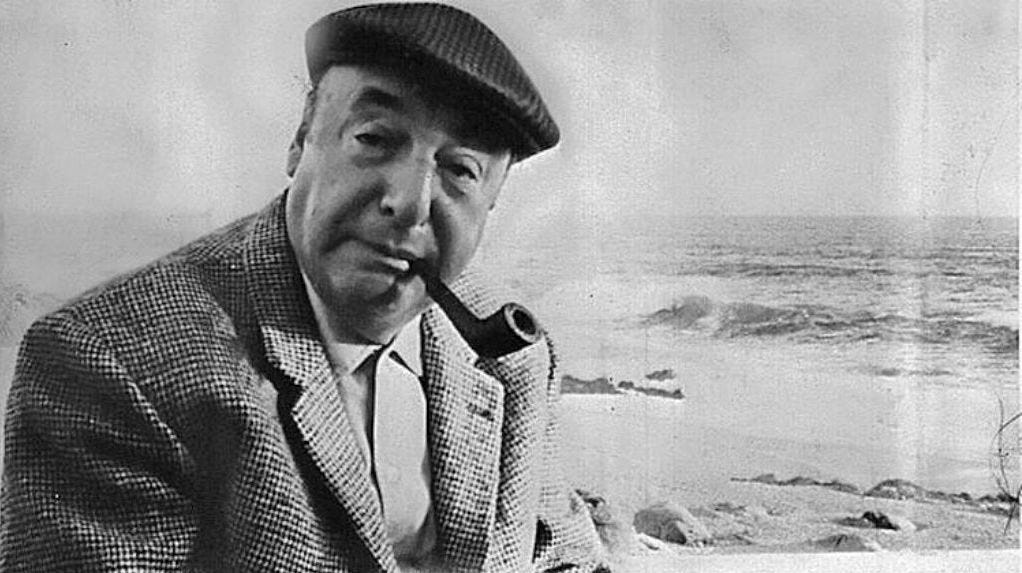

Look at this one. These are a few lines from a love poem by Pablo Neruda, but don't worry about that. Let's just read it slowly, without trying to understand it. Just listen to the words.

Here I love you.

In the dark pines the wind disentangles itself.

The moon glows like phosphorous on the vagrant waters.

Days, all one kind, go chasing each other.The snow unfurls in dancing figures.

A silver gull slips down from the west.

Sometimes a sail. High, high stars.

Oh the black cross of a ship.

Alone.Sometimes I get up early and even my soul is wet.

Far away the sea sounds and resounds.

This is a port.

Let the words echo for a little while more. Keep them in your mind, like the aftertaste of something nice, a sweet, a fruit, or a drink that you like. Perhaps you already found this enjoyable. Or perhaps you are saying, like my daughter would, “I don't understand this.” But have patience for a moment longer.

Rational understanding is not the only way to relate to the world and to receive input from it. The way we live now, with all the media that bombard us with content all day, we are very much trained to immediately look for the message, the “point” that is made, the one bit of information that we need to extract and use.

But for much of human history, this was not the case. Much of what we see and hear today is words — information that is naked, removed from its context, ready to be processed and consumed. But imagine how it was in old times, before most people could read. If you were a farmer, you would go out to your fields in the morning. You would work there in silence, listening to the wind, the birds, the insects. You would see the sky, the trees, the mountains, your crop.

All these things would actually give you information, but of a much different kind: it would be indirect, hidden within the world, in need of being decoded. The wind and the colours on the mountains would tell you how far the season has come. The clouds would tell you of the weather. The insect buzz would give you information on how healthy the environment was, on how well your field is being pollinated. The birds, their cries, the species you can see and hear, their flight patterns in the sky — all these things would tell you more about the world around you, about how the year is going along, about when to expect your harvest and whether it will be a good one or not. You would not have a calendar or a phone app to tell you the time or the season. You would have to understand your place within your world by yourself, by using these cues, by feeling the passage of time, the changing of nature, by reading it off a myriad little observations.

But it wouldn't be “reading,” really. Again, modern language fails us. You don’t “read” the book of nature. You “feel” it. It's not a process of decoding a linear flow of information, like the one you’re listening to now, but of taking in a whole picture at once, the whole state of the world that surrounds you in one particular moment, and letting your senses, your subconscious, your instincts take over and do the understanding. The result of this process will be a feeling, not a piece of hard information. It will be a feeling situated inside a particular context: YOUR feeling, from YOUR field, about YOUR future plans and YOUR concerns, based on YOUR experience and YOUR past. You won't get context-free advice in this way, and you wouldn't want any. You want your understanding of the seasons and the harvest to apply to YOU and YOUR field, YOUR family, YOUR world — you'd have no use for an abstract list, for information that is not tailored to YOU and YOUR life at this exact place and this exact moment in time.

What does all this have to do with poetry?

The same sense of feeling something happening that the farmer has, is exactly what allows us to feel poetry and art. Think of an abstract painting like this here:

You cannot “understand” that logically. And even if you could, if you dissected the way it is painted, the brushes used and so on, you would still miss the point. You are not supposed to analyse it. You must look at it like the farmer looking at the sky — and let it speak to you in its own language, in its own way.

I think of it as tasting the words of a poem, or the image on a painting. When you experience a bite of food, you can do it in two ways: You can either ask yourself: “How was this made?” and try to analyse the ingredients, guess at the way of preparation and how the cook achieved the particular effects that make this food special. Or you can just close your eyes and enjoy it without asking anything at all. The second way is not worse than the first — arguably, it’s better, bringing about more enjoyment in the moment, not less.

Let's look at another poem. This one is by Paul Celan, who is generally considered “difficult” to understand. He is, but the whole point is not to try and understand him. Instead, try to get into a dreamy state where you listen and see the images pass by your mind, without trying to make rational sense of them. Here we go:

The stone.

The stone in the air, which I followed.

Your eye, as blind as the stone.We were

hands,

we baled the darkness empty, we found

the word that ascended summer:

flower.Flower - a blind man's word.

Your eye and mine:

they see

to water.Growth.

Heart wall upon heart wall

adds petals to it.One more word like this word, and the hammers

will swing over open ground.

I know that some will say that you do need to understand these poems. They are coded messages about the Holocaust perhaps, or about other events in the poet’s life, and not trying to understand them devalues the poetry. People who say this usually work at literature departments of universities and make a living off explaining poems to others. And I won’t entirely disagree. There may be multiple layers in a poem, some of them purely rooted in the image, some of them in the sound of the words, and some again in their meaning. That’s fine, and if you can get enjoyment or insights from understanding the hidden meaning, then go ahead.

Here I'm not talking to those who are already experts in reading and understanding poetry. For the person who just encounters a poem like that for the first time, it would be bad advice to try and understand every word and every hidden meaning in it. If the poet wanted us to do this, they would have written the meaning out, rather than those images and words that they used. Some people do that, and what they produce is called an essay or a pamphlet, or an instruction manual. But not a poem. The mystery of the language, the richness of the images, the hidden meanings — these are all necessary parts of poems of this kind, and it would be a waste of the poet's effort to strip his work of them in order to just “understand” them.

Let me show you another one, this one from a Greek poet I love, Yannis Ritsos. As with all these poets, translations often ruin the work, but we cannot do much about that. Not reading Neruda, Celan or Ritsos at all, because they don't write English, would certainly be worse than to read them in translation.

So, here we go:

Forgetfulness

The house with the wooden staircase and the orange trees,

facing the azure, big mountain. The countryside gently

walks around inside the rooms. The two mirrors

reflect the singing of the birds. Only

that in the middle of the bedroom lie abandoned

two fabric slippers for the old. So,

when the night falls, the dead visit the house again

in order to collect something of theirs left behind,

a scarf, a vest, a shirt, two socks

and then, possibly due to short memory or carelessness,

they take along something of ours. Next day,

the postman passes our door without stopping.

Listen to these words, these images, listen to their taste:

“The countryside gently walks around inside the rooms.”

“The two mirrors reflect the singing of birds.”

Why are the dead careless? Why have they left behind a scarf, a vest, a shirt, two socks? Nobody knows. But it doesn't matter. What matters is the sound of the words, the echo of the images in one's mind, the nameless things that one can take away from it all.

Some kinds of poetry speak to us as the sky and the hills spoke to the farmer of old. There is nothing to understand and everything to just stop, and be silent, and listen to.