Note: This is a pretty long article. If it gets cut off by your email client, simply click on the title of this piece and you will be redirected to the website where you can read the full article. Thanks!

Can we escape fate? Are we free to determine our own destiny, our own path through life? Or are we just pawns pushed around by forces we don't understand? Meet Walter Faber, a man who believes in logic, reason, and in engineering his own destiny. Max Frisch's Homo Faber is not just another novel; it's a modern reenactment of ancient tragedy where every rational choice leads to inevitable doom.

Hello, welcome back. My name is Andy, and today we are going to talk about a book that is immensely timely. It is a book that talks about tech growth, about technology, and the effects of technology on human beings, on the soul of human beings. But it does this in 1957, at a time when you would not expect this. So, it's an immensely prophetical book. It is also a book that really captures both the essence of ancient Greek tragedy and the essence of what technology does to us in a modern tale.

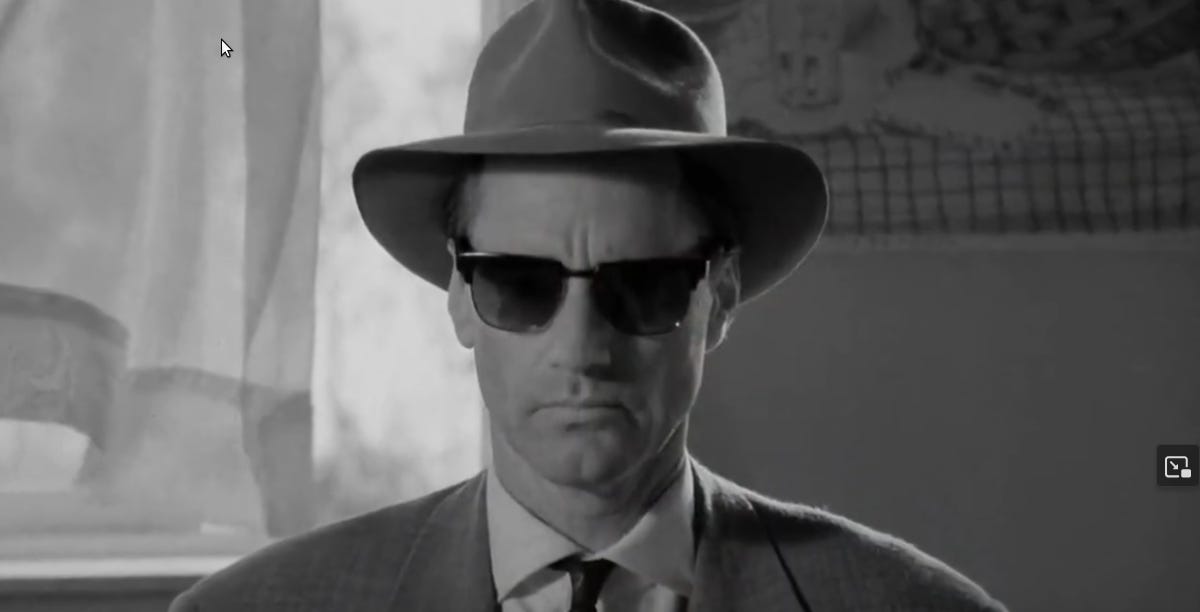

The book I'm talking about is Homo Faber – Homo Fay-ber, you would say perhaps in English – by Max Frisch. Max Frisch was a very influential German-language author, Swiss in fact, who mainly wrote in the '50s, '60s, up to the '70s. He was perhaps one of the biggest names of German literature throughout the '60s and is still taught in schools. His books are very important, very influential, very much talked about. And this book is one of his most famous. There was even a movie made from it, an American movie actually, with American actors – an international production, partly German, partly French, I think, partly American. It was released under the title "Voyager" in the US.

What Does "Homo Faber" Mean?

You know "homo" means human – Homo Sapiens, the wise human, which is our biological self-designation as a species. And "faber," the second part, is related to the word "to fabricate," "fabrication." "Fabric" means something that is artificially made. And so the term Homo Faber is sometimes used in anthropology, in history or in sociology, as the concept that human beings can be seen under this perspective of being toolmakers, tool-making animals. Homo Faber – fabricating animals.

Because other animals – this is at least the assumption there when we use the word – any other animals don't do that. It is not entirely true; crows are known to use tools, apes can use sticks to get bananas from the tree, so they are using tools. But undoubtedly, human beings have a much greater capacity at this. We can not only use tools that we find, but we can fabricate tools. We can fabricate very complex tools or tools for multiple steps that we are going to use in a very remote future. We can fabricate tools for other people; we can make factories which then will produce other things. So, we have multiple levels of tool use, and industrial societies are all based on this idea of fabricating things. And in this way, our whole modern world is a world of fabricating things that started, of course, with the Industrial Revolution back in England. We are defined as being Homo Faber, as being tool-making animals. You cannot think of human beings in any other way. Of course, we have many other properties, but if you look around your world, if you just look around your room, it's full of things that we have fabricated. The room itself, the house is fabricated. None of us live in caves that occur naturally. Behind me, I see a shelf of books; in front of me, the light that shines on me; there's a microphone; there's a camera. We are surrounded by our fabrications. We are tool-making animals, we are tool-using animals.

And so Frisch sees the essence of the human being as being Homo Faber. And in this tale – because this is not an anthropological or philosophical book, it's a tale – he begins with a particular person who represents this thing, this Homo Faber. Today, we would say Elon Musk represents the ideal Homo Faber: somebody whose whole life is dedicated to fabricating stuff, artificial stuff that is supposed to make life better or more interesting, or to eradicate disease or to bring us to Mars – all these big promises of industrialization. Zuckerberg from Facebook (Meta) is another Homo Faber. We are surrounded by them; there are many, many like that. Even Bill Gates, you can say, is a Homo Faber. Every industrial person, every software developer defines themselves, defines their life through their work with machines, with artificial things.

But it's important to see that although today we have all these big personalities that represent technology, and even the dangers of technology, in reality, this is a very old thing. Technology always existed. The ancient Greeks had technology: they had writing, they built temples, they had lots of artificial structures, they had weapons, military technology. And particularly, of course, throughout human history, all kinds of technologies for everyday life: we had mills, we had windmills, we have water mills; we have again, technologies for war, we have ships, we have technologies of discovery, we have books, we have libraries. These are all technologies.

And then there was this explosion of technology in the 18th, 19th century, what we call the Industrial Revolution. This was a big boost in technology and in the way we relate to technology. And this took away from us almost entirely our non-technological life that we had before. So after the Industrial Revolution, we are all married with technology, almost necessarily. It's almost inescapable. There are few individuals who try to live without technology; they go on their homestead and live without electricity and without modern conveniences. But these are so prominent because they are so rare that we watch videos about them and about their lives, and they are on YouTube – perversely again, using technology in order to show us how well they live without technology. And everybody else is just totally embedded in this technological world.

The Question Frisch Asks

Now the question is: what does this do to us? And this question Frisch asks in the '50s, the end of the '50s. And you have to see that this is a big time of engineering back then. In the '50s, after the Second World War, was the time when the West, especially Western Europe, was rebuilt. The United States didn't need rebuilding because they had not suffered destruction on their own soil. And they had the wealth that came from being the winners in the war. They had machines, they had all this technology that was developed throughout the war: primarily airplanes, landing strips, tanks, cars, vehicles of all sorts, food technologies. And now they took all these technologies and they applied them to everyday life.

And suddenly there was this sense of a new explosion, a new age of industrial revolution. You can see this in comics, in The Jetsons and other such visions of people living in this jet age. The jet age itself – jet engines are from this time, end of the Second World War. The first jet engines for airplanes, air travel, which made it possible to travel very quickly, much faster than ever before, and the decline of ocean voyages in favor of airplane voyages. And there was this feeling that we are going into a science fiction world. You had all these science fiction exhibitions, and science fiction itself took off in the '50s. And it was the big time of science fiction. If you look at all these writers – Bradbury, Clarke, Asimov – these all flourished throughout the '50s, '60s, which was the time when people were hungry for technology to change their lives for the better, to bring us into some utopian world. You had concepts of space stations back then, flying to Mars, having these big space stations like you see them in 2001: A Space Odyssey, the Kubrick movie.

And then, of course, you had the Apollo program, flying to the moon. And flying to the moon was the big thing. Kennedy at the beginning of the '60s saying that in 10 years we will land on the moon. And I make this promise, I make this plan, I commit us to landing on the moon by the end of the '60s. And they managed. They went to the moon, and they paid a ton of money for it. And they developed all the technologies that were necessary, almost out of nowhere. And within 10 years, a man was standing on the moon. So this is an explosion of technology. This is a belief in technology, the power of technology to make us better. Not only to bring us to the moon in a way like a transportation achievement, but to make our lives better, to make our relationship with the world better.

And this is also expressed then – and now we come back to the book – in terms of development help to other countries, which also started after the Second World War. The idea that rich countries help poorer countries, not by colonizing them, but by providing technical help. So you have UNESCO, you have the UN, and all kinds of UN development programs sending engineers from the West and tools from the West and machines from the West, from the rich countries to the developing countries, where they will be used to improve the lives of the people in these developing countries.

Meet Walter Faber: The Enlightenment Engineer

And this is exactly where we are in the book Homo Faber. We have this person, Walter Faber. That's his name. And he is a German (Swiss?) originally, living in New York now, and he's an engineer for the UN (UNESCO in the novel). He's traveling around, sent by his company who develops machines for the developing world. And he's sent around to various places in the developing world to install and oversee the operations of these machines. And so his job is very much the job of this enlightenment engineer, somebody like an Elon Musk, who is convinced that his work directly contributes to the bettering of humanity, to making the world better, to improving it, to saving lives. And he really believes in it. He has an almost religious belief in technology, in science, and he refuses to engage with anything else.

And now this is important because we come to this point where we realize very soon that Walter is not able any more to engage with human feelings that are outside of the sphere of technology. And again, much like today, we have these tech bros who seem to be stuck in their world of technology, unable to perceive any problems outside of their technology, who believe that everything can be solved through technology. And Walter Faber is like this. He's a person who cannot have a normal human relationship. He has a girlfriend, but he only meets this girlfriend in order to satisfy some social needs. He is not himself attached to this girlfriend, although she is to him. He is never afraid of the dark, for example. He says, "Why should I be afraid of the dark? There is nothing to be afraid of. Dark is just dark." And people who see ghosts in the dark, they have a problem; this is not rational. And when he sees something beautiful, a sunset, he says, "Okay, I know why the sunset is red — it’s because this is the CO2 from the air and the light is refracted and scattered in particular ways that make the sunset red. But there is nothing to it. There is nothing to admire. Why should I admire the CO2 content of the atmosphere and call it a beautiful sunset? What does it even mean, beauty? What is beauty?"

So Walter Faber goes through life in this way of detachment, of scientific detachment, of calculating everything, of knowing how things come about. In a way, he is a superior man in this tech bro way because he is superior to his own feelings. He is not a slave to passions. He is somebody who is cool, detached, superior to the world also, at least he thinks so, because he understands the world in a way others don't. When he's in an airplane — and the story begins in an airplane — and the airplane is shaking, others are perhaps afraid for their lives. He is not, because he knows how much load the airplane wings can take and when the shaking will become too much. And all this is rational thought that keeps him from being afraid.

The Unraveling Begins

And now for the rest of the book – and this is the nice thing about the story, and don't forget we are not talking about a non-fiction book, we are talking about a story, we are talking about a novel, and a very gripping novel, a beautiful novel – the novel begins with this weird man, Walter Faber, who is stuck in this way of seeing the world. And now the rest of the novel, the whole program of this book, is to deconstruct Walter Faber, to show him that the world is not as he thinks it is, to show him that a human being cannot live in this way, that we are not like that.

And Frisch goes on a confrontation course with this character Faber that he invented. He confronts him with all sorts of disasters, step by step, little by little, until the life of Walter Faber unravels and becomes worse and worse and becomes unbearable. And he reaches a point at which his world collapses.

The story begins in an airplane. Walter Faber is flying. And it is the genius of Frisch that, from the beginning, we see immediately how Walter Faber sees the world. He looks out of the window, he sees the moon, he sees the remote hills and mountains along the way out of his airplane window, down there in the hazy purple light of dusk. And instead of seeing all these things, he sees just hills, he sees colors, he sees the scattering, like I said, of the light. And he says, "Why are people so crazy about this? Why do people see things so poetically? You don't have to do this. You can just say, 'These are hills, this is an airplane, I'm looking out of the window.' And that's it."

And beside him sits a man, a Swiss businessman. And the two play chess after a while to pass the time. Remember, this was written in 1957, so probably it is 1955 or something in the story. So this is a time when airplanes could not yet fly non-stop across the continental United States. So they are landing at some point to refuel. And when they land there for refueling, the first unusual thing happens. Suddenly, Walter Faber has the feeling that he does not want to continue. He doesn't feel well. He feels dizzy, he feels sick. He goes in the bathroom, he waits it out, and he misses his plane.

He goes out and somehow he's relieved to have missed the plane. He doesn't understand why. He distrusts his feeling because, as we said, he tries not to have any feelings. So he feels bad about missing his plane, but he knows there's another plane, there's no problem, he will get the next plane. But then he meets a stewardess from his plane who is still looking for him. So he has not actually missed his plane. The stewardess grabs him and pulls him onto the plane, although he feels that he doesn't want to. He feels this resistance.

And what happens next, you can imagine: the plane crashes. And so this premonition was actually the premonition of this thing that was going to happen. And this upsets him because this whole thought is alien to him, because premonitions don't exist. Premonitions are not scientific. He shouldn't have them, and this shouldn't have happened. The whole crash shouldn't have happened, because airplanes are safe. But anyway, it happened. And the crash itself can be explained in mechanistic ways; it can be explained with science. So he's not unduly upset by the crash itself. He takes it cooler than the other people on the plane. Nobody is injured, there are no deaths. The crash is a very soft landing in the desert. So now they're sitting in the desert, everybody is fine. They get out of the airplane, they have drinks, they have food, and they spend a few days waiting to be rescued, while they are relatively comfortable there in the desert.

And this is used again as a way for Frisch to show how Walter Faber sees the world. After a while, they are rescued, they are brought to their destination. But then Walter Faber finds out that the person who was sitting with him in the plane, the Swiss businessman, is somebody who knows people from his past, people Walter Faber studied with in Zürich in Switzerland long ago when he was a student. And so they become friends, and they decide to continue together. And although Faber is always busy denying that this plane crash affects him emotionally, we see that he is shaken. He doesn't want to go home, he does not want to continue his normal life immediately. He does not want to go to his engineering job with the UN where he was originally going to. He needs a break.

And so he goes together with this man who was in the airplane, his seat neighbor. They go together, they rent a jeep, and they go to find the friend of Walter Faber's youth, Joachim, who now is in this Latin American country and has a farm somewhere. And so suddenly they find themselves – although Faber is always so rational and so calculative and so unemotional – suddenly he finds himself in a South American jungle on a jeep together with a person he barely knows, looking for a friend from his past. And this is the beginning of this unraveling. And they go and they find the friend from his past, but unfortunately, this friend has committed suicide on his farm. And this is another blow to Walter Faber. Suddenly it's not only seeing his friend from the past, but it is witnessing the death of his friend from the past and seeing that the world is not as he thought. The world is not this well-ordered thing where everybody goes on their orbits like planets. The world is a place that can be dangerous, that can be unpredictable. It's a place where you can die. And this is the next shock.

This article is getting too long for an email, so I’ll stop here and we continue next time! If you want to know what happens next without waiting, you can watch the video linked at the top, which tells the whole story! :) — See you next week!

— Andy

Update: The second part of this article is now here: