Why Are We Unhappy? #045

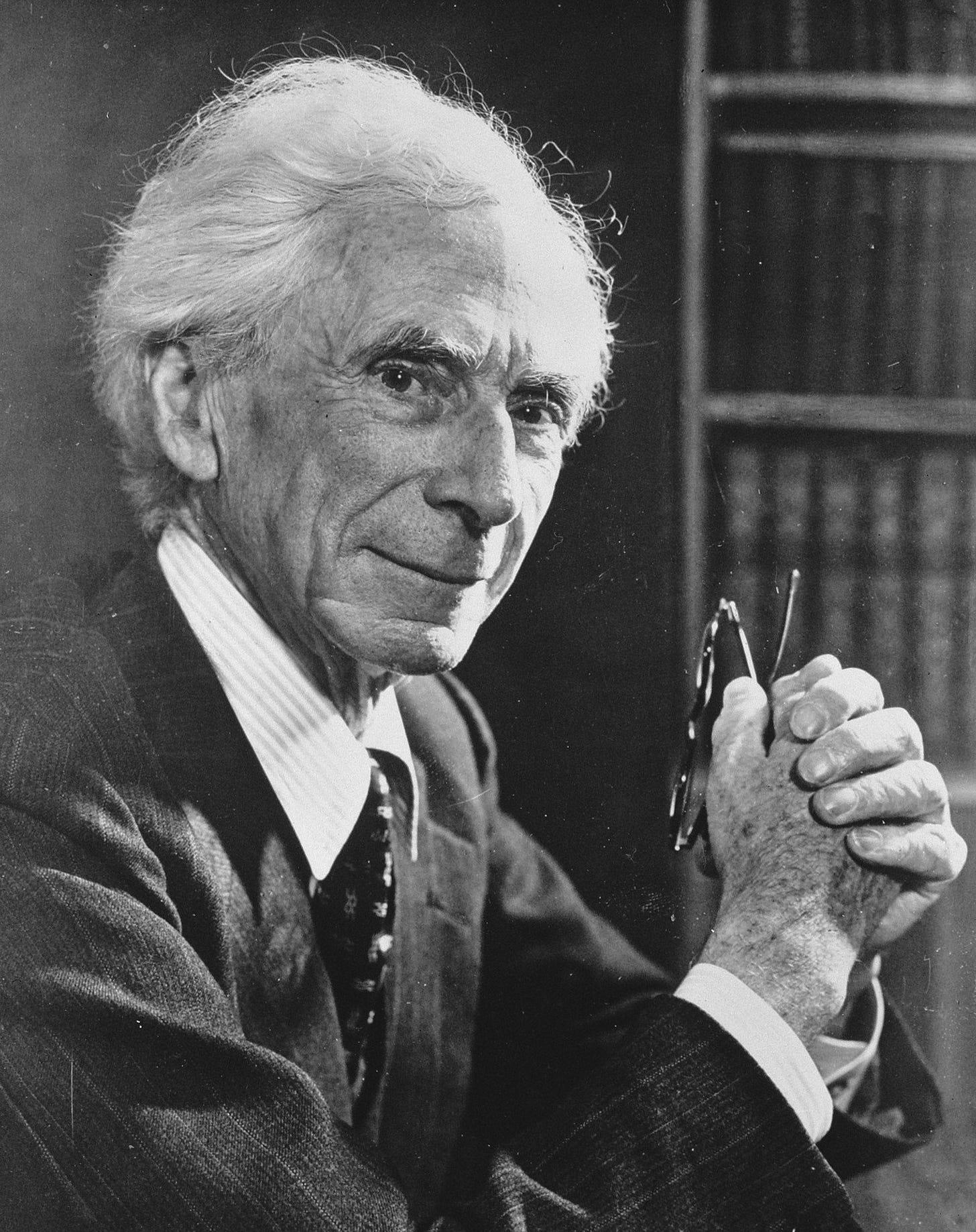

Bertrand Russell's Conquest of Happiness

Hello and welcome again to Every Dawn!

I think that some of you might feel a sense of déjà vu because we have already discussed these topics in some of the other channels of daily philosophy. I have written articles about them, we have the podcast where some of these things have already been discussed, and we have the two YouTube channels where I have also made videos in the past about these topics. So, if you have heard these things, then forgive me for a few sessions now. We will be talking about things that I have talked about before, but we have many new viewers and listeners, and therefore I think that it's worth repeating. And perhaps, you know, you have also forgotten it and then it won't hurt to talk about these things again.

We have been talking about Aristotle. We finished talking about Aristotle's theory of happiness, and if you want to learn more about it and if you just recently joined, then you can go back and watch all the previous videos. Now we want to proceed with modern interpretations of Aristotle, of which perhaps Bertrand Russell is one of the most influential.

The first question that Bertrand Russell asks in his book The Conquest of Happiness from the 1930s is why are we unhappy in the first place? Because if you look at our lives, we are, for the most part—of course there are exceptions—but most of us are relatively well off. We are not threatened by horrible diseases or famines, we have clean water, we have food, we have safe houses, we have societies that are largely safe, and so we are not really in any danger. We have lives that are materially good, at least sufficient, and in many cases, they are very comfortable. So objectively, there is no reason why we should be unhappy.

Russell compares this with animals, and he writes, "Animals are happy so long as they have health and enough to eat. Human beings, one feels, ought to be, but in the modern world, they are not—at least in a great majority of cases." So why is this? Russell goes and tries to find out what is the reason that we are so unhappy.

Bertrand Russell, one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century, generally more known as a logician, is not so much a philosopher of happiness, but he did write this one book where he tried to apply observation and logic, and a scientific approach, you could say, to the study of happiness, which today, of course, we have lots of, but back then in the 1930s, this was a new thing.

He diagnoses a few things, and one thing he says is this fashionable unhappiness, he calls it the ironic unhappiness from Lord Byron—today we would say cool unhappiness or influencer unhappiness. This is the unhappiness of a poet, of an Instagram influencer, of any media person where it is part of their coolness to look unhappy, to look suffering, because they have understood how the world works, and they have looked through it, and they have understood that everything is suffering, and therefore, now they wear this mask of suffering which is part of their public persona. You could say it is not only the case that this is a role—it is not always only an Instagrammable pose—but sometimes it is genuine.

We also sometimes feel like we are fed up with the world or like the world doesn't have any meaning, and especially when it goes into, you know, depression—not of course clinical depression, this is something different that needs treatment—but this everyday depression. We have this weariness with the world, the um, you know, dislike of waking up in the morning and getting out of bed because we realize that the day will be the same as the day before.

And what can we do about that? Russell thinks that generally unhappiness is a misunderstanding, it is an error, it is not something that happens to us but something that we can actually change by seeing the mistake and then correcting it. He writes, "I believe this unhappiness to be very largely due to mistaken views of the word, mistaken habits of life, leading to destruction of that natural zest and appetite for possible things upon which all happiness, whether of man or animals, ultimately depends."

Now, about animals, it's hard, of course, to reason—we don't know what the happiness of animals is doing—but it is plausible that the happiness of human beings depends, to some extent at least, on this feeling of curiosity about life. And this is the main thesis of Bertrand Russell.

But now, let's go back to this idea of unhappiness, of getting out of bed in the morning and feeling that there is no point in continuing because the world is only going to be the same again as it was yesterday, and it's just all a waste of time. Here, he says, if we look at how this comes about, this kind of unhappiness, this kind of mild depression, the reason is generally that we don't engage enough with life itself.

And so, he writes, "I have frequently experienced myself the mood in which I felt that all is vanity. I have emerged from it not by means of any philosophy but owing to some imperative necessity of action. If your child is ill, you may be unhappy, but you will not feel that all is vanity. You will feel that the restoring of the child to health is a matter to be attended to regardless of the question whether there is ultimate value in human life or not."

So, when we feel this boredom and this emptiness in our lives, it is, he says, because we don't engage sufficiently with the world. If something forces us to engage, like a sick child, then suddenly we jump back, and then suddenly we know what we have to do, and then all these thoughts disappear, and the imperative of action, you know, grabs us, and we have to do something.

Russell thinks that we can also promote this without having sick children by ourselves, creating situations in which we are more active. So, for example, he writes, "Go out into the world, become a pirate, a king of Borneo, a laborer in Soviet Russia. Give yourself an existence in which the satisfaction of elementary physical needs will occupy all your energies."

And this is something that makes sense, and of course, many of us have done this. This is why I think the survival shows, for example, on YouTube, are so popular because, in a survival situation, you have exactly this—you have all these immediate needs, and you don't have time to brood or to think, you know, about the meaninglessness of life.

And the same is true of, you know, milder survival-type situations, let's say van life, which is also an immediate engagement with the things around you, or even something perhaps like tiny home living. So just imposing these limitations that make it necessary for you to engage more with things rather than being in a very comfortable bubble where you can just sit on the sofa and do nothing. So, the more manual our life is, the more engaging it is, the less we will be unhappy—at least, this is Russell's idea.

So perhaps today, we can just see where in our lives we have situations where we are perhaps a little too comfortable, where our life does not provide any challenges. This, of course, will be mostly at work because most of the work we do is just boring and repetitive for most of us. But it will also be perhaps at home, in the way we structure our free time. Just sitting in front of the TV is not particularly challenging; sleeping is not challenging, and perhaps we can replace one or two of these things with something that gives us more of a challenge.

And this shows you, you know, back to Aristotle, that gives you more experience and more possibilities to exercise your virtues. So let's say something easy: go out to the streets and find somebody you could help. You know, help somebody across the street, or give some help to some homeless person where you can perhaps give them some money, or perhaps you can talk to them, or in a more organized way, instead of doing it alone, try to see if there is a charity in your city where you can go and help for 1 hour every Friday afternoon.

Right, there are these things—I have done this myself, and it is interesting that if you think of this movie, Groundhog Day—I don't know if you remember this with Bill Murray—where he lives the same day again and again and again, and he's trapped in this repetition. And what is the way out of the repetition? The way out is to be helpful to everybody, and then he goes out of this, and then he finally reaches happiness.

And I think this speaks to the same idea that if we want to be happy, we need to be active, and we need to have the sense that our activity is appreciated, that it is useful, that it is producing a difference in the world. And this is what both Aristotle and Russell are saying.

So, thank you, and see you again tomorrow.